Firstly, an apology for not writing my monthly slot on this

blog throughout the summer. A

combination of having to frantically meet my publishers deadlines for my local

history book, coupled with the long school summer holidays and having to “entertain”

my son put paid to my blog writing activities.

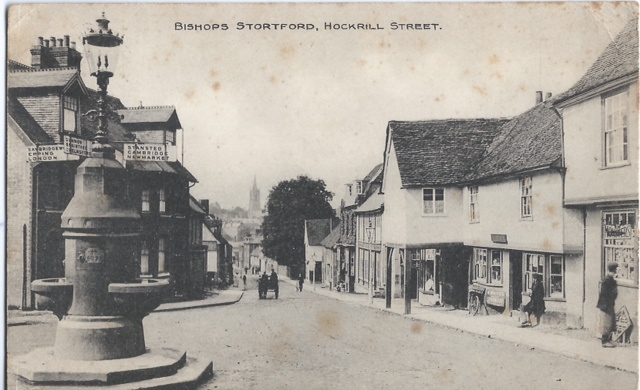

But, I am now pleased to say that my local history book

Bishop’s Stortford Through Time is now

available in the UK on

Amazon (book and Kindle); and will be released on 28 September on the

American Amazon.com. I have

yet to see my own copies of the book, but from the proofs of the book, I am

very happy with the result.

Are our female ancestors 'hidden from history'?

Whilst researching my book, I discovered several “family history” stories about local

people and was able to incorporate some of them into my book. One story which stood out to me was about a wealthy

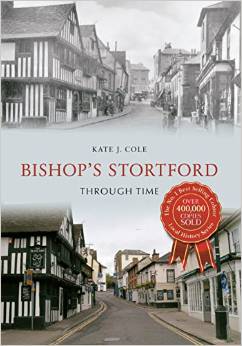

Victorian childless couple who gave to the town of Bishop’s Stortford a very grand

water-fountain. This water fountain was

installed in the 1870s at a very popular and busy crossroads in the town; and

used by many weary Victorian and Edwardian travellers. Whilst researching this story, what struck me

the most was that, although the inscription has on it the names of a husband and

wife, Edwin and Eliza Eyre, it was highly likely that the bequest to the town was

the result Eliza’s money. She had been

left a substantial amount of money by a very wealthy uncle, and it was probably

this bequest which resulted in the gift of the water fountain to the town. As the uncle’s bequest was in the

late 1860s (i.e. before the Married Women’s Property Act of 1870 and 1882), legally her

money would have belonged to her husband, Edwin Eyre.

|

| The Eyre's water fountain - Bishop's Stortford |

I have read several other accounts of Bishop’s Stortford’s water fountain, and in all other accounts I’ve read, Eliza’s financial contribution has been ignored, because researchers automatically assumed the gift to the town was from Edwin’s money.

The story of the Eyres brought home to me that when conducting genealogical or family history research, the female line cannot be ignored. Yes, it is sometimes harder to find our female ancestors, but they are very rarely totally “

hidden from history”.

My great-grandmother - Louisa Parnall

One such female ancestor that has intrigued me over my years of research is Louisa Parnall – my paternal great-grandmother – the mother of my grandfather – and her family. The Parnall family has long fascinated me (always spelt Parn

all, never, ever with an “e”). But, I have always found it very difficult to retell their particular story because there just is so much evidence about them and their activities. I have a mountain of information, documents and photos about them all. It's that rare occurrence when there is simply too much evidence about a particular family to make it all into a coherent story!

|

| Louisa Parnall - shortly before her 1880 marriage |

The Parnalls from Llansteffan, Wales

In a nutshell, four brothers and one sister left the tiny rural village of Llansteffan, in Carmethenshire, Wales sometime between the 1820s and 1833 and headed for the bright lights of London. The two younger brothers and the sister (Robert, Henry and Anne) found that the pavements of London were, indeed, lined with gold and so made their fortune in the clothing industry. They ultimately died with enough wealth to make them each the equivalent of today’s multimillionaires.

Sadly, the two older brothers (William and Thomas), did not make their fortunes, and so both, at different times, were made bankrupt and thrown into debtors’ gaol. Both, probably as a consequence of their financial misfortunes, died relatively young in their 40s/50s. William was my 3x great grandfather – Louisa being his grand-daughter. Fortunately, the successful siblings looked after William’s many children and grand-children – employing some of them, making others their heirs, and leaving substantial bequests in their wills to all of them – including my great-grandmother (their great-niece). Thomas appears to have not married and died childless.

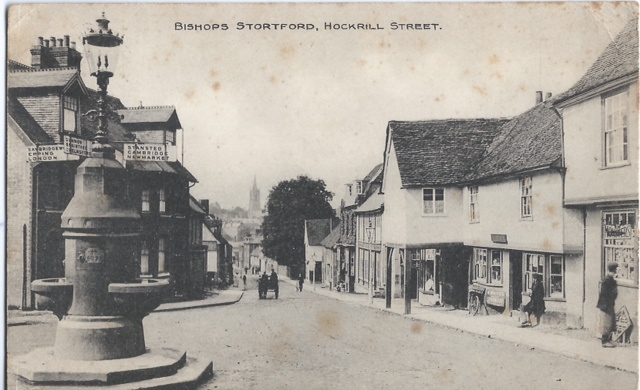

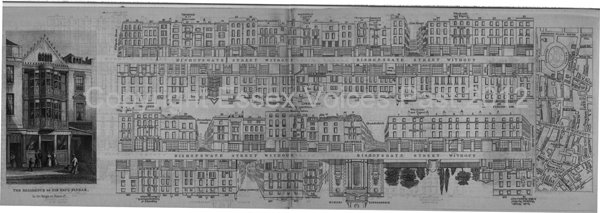

When researching the story of the Parnalls, it has always been very easy to track down Robert Parnall and his brother Henry Parnall because they had a very large warehouse/factory in the City of London (Bishopsgate) and in Suffolk, and employed many hundreds of people. I have even tracked them down on Google through a very tenuous link that one of Jack the Ripper’s (suspected) victim’s lovers worked for them! Even poor William and Thomas Parnall can be tracked down via Google because of their bankruptcies.

|

Tallis’s London Street views - Bishopsgate Without (1838-1840).

The Parnall's first factory is shown at number 100. Ultimately they had 2 factories on this very busy London high-road. |

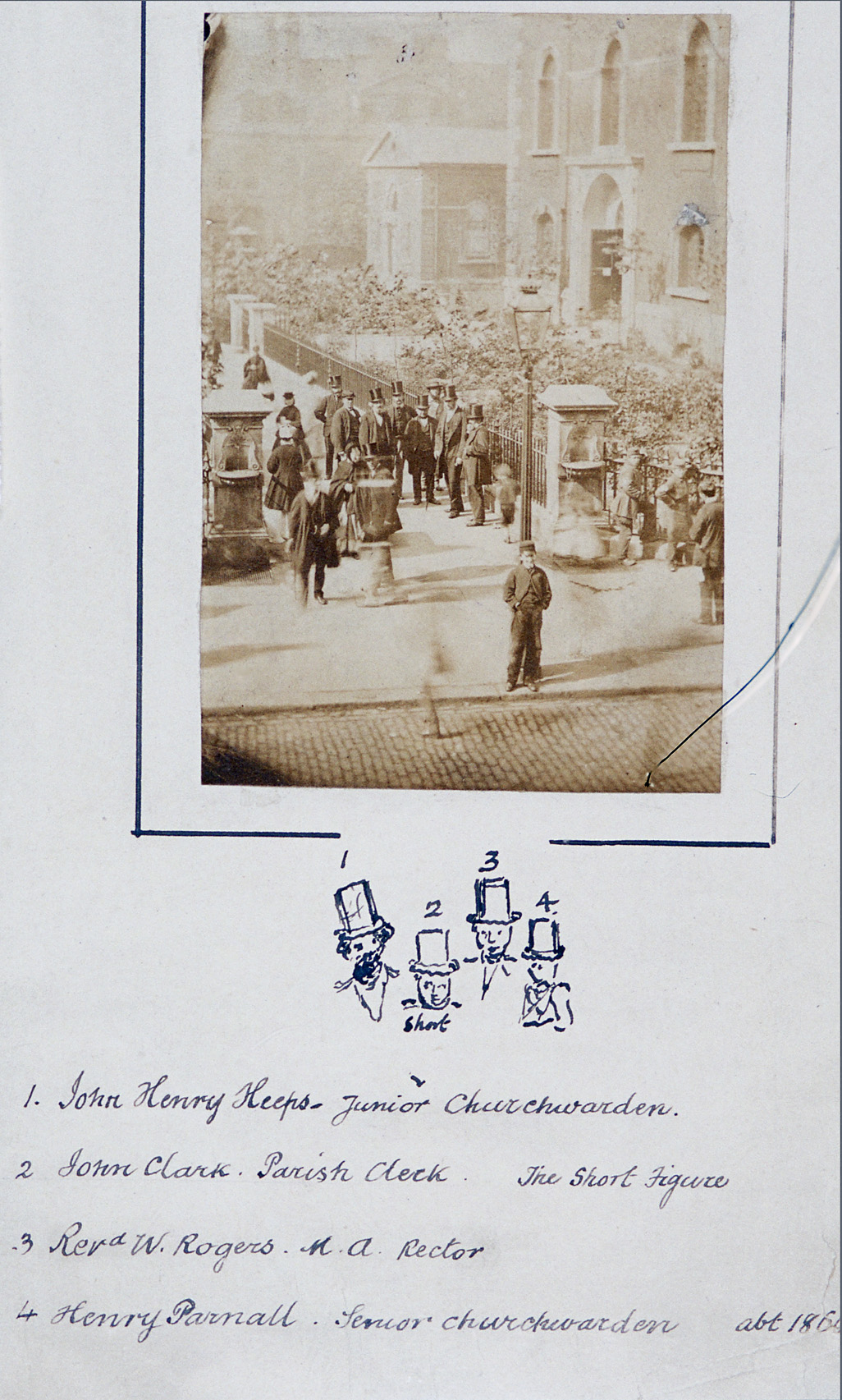

|

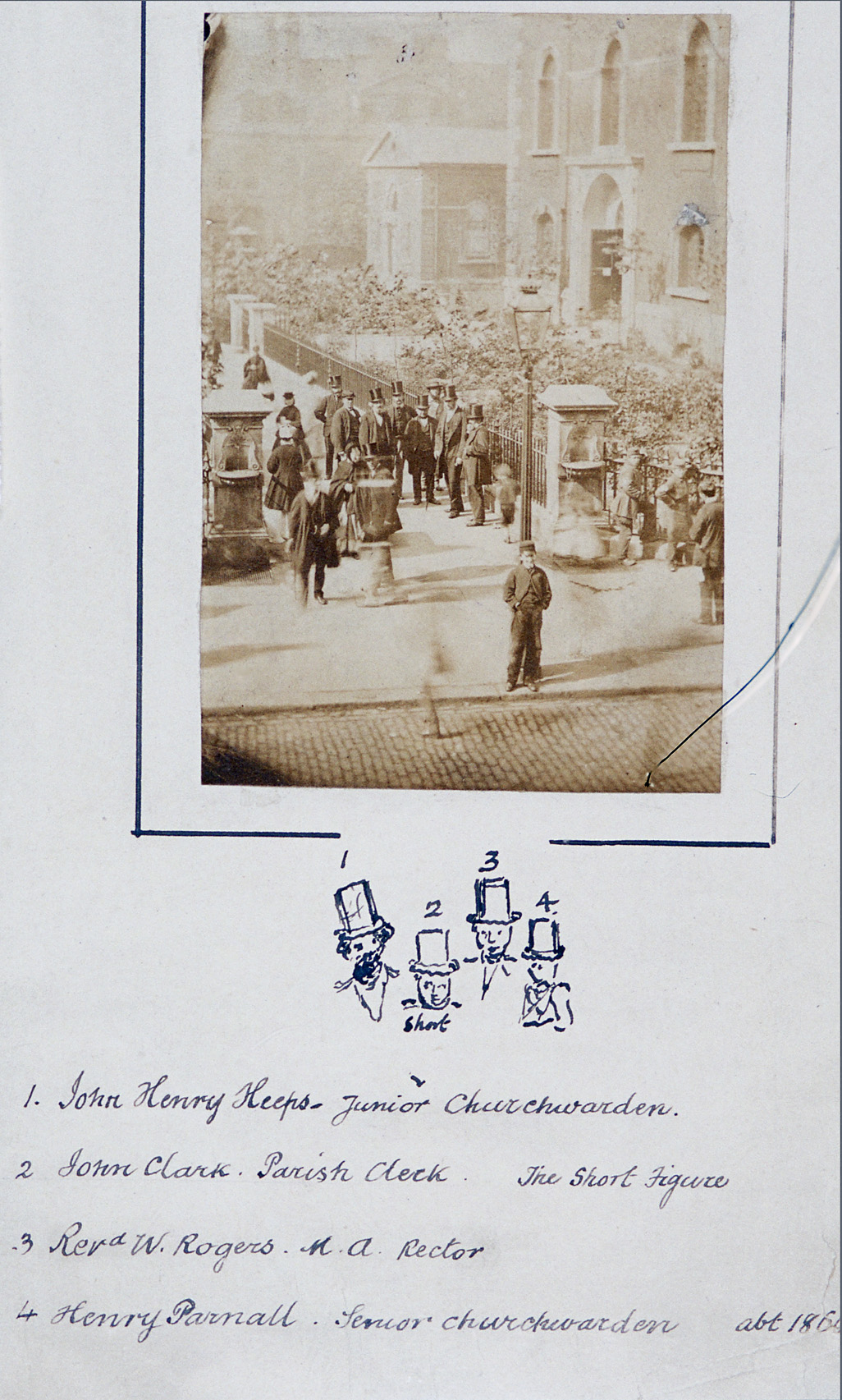

Henry Parnall in 1860 in the churchyard outside St Botoph's Church, Bishopsgate.

He left a substantial will bequest to St Botoph's Church for them to maintain their graveyard as a garden for use by the general public. Thus my ancestor has ensured that many of today's City-workers have somewhere to sit in the fresh air on a sunny day.

Image appears by kind permission of City of London's Collage Collection |

But over my many years of research into the Parnalls, I’d totally ignored their wives.

The wives of the Parnall brothers

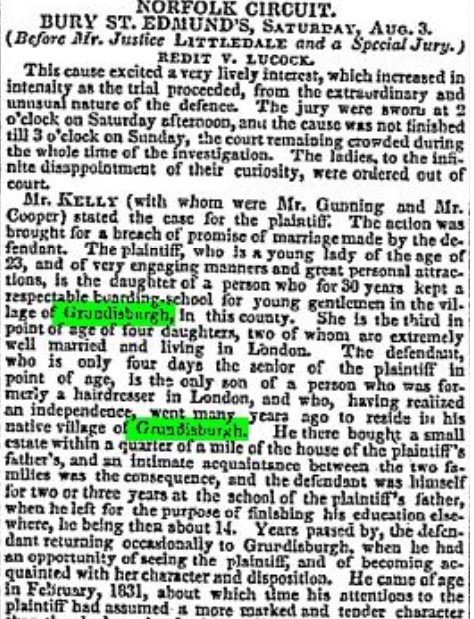

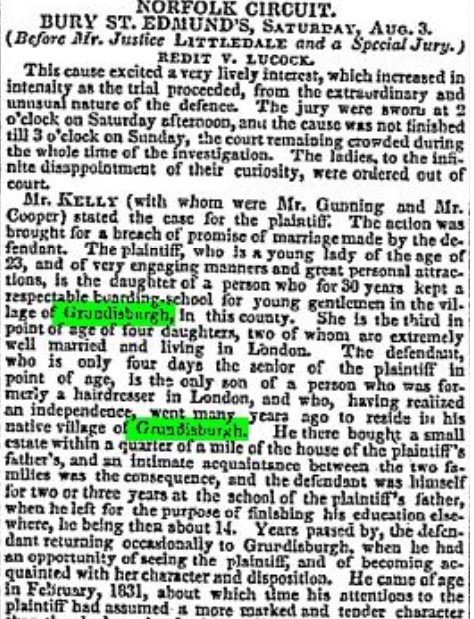

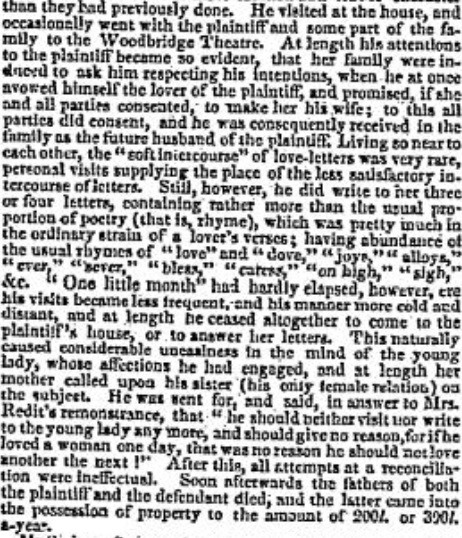

A few years ago, the British Newspaper Archive came online and a whole new world of genealogical research opened up – newspaper articles. So I started entering in my Parnall names, and as expected, found plenty about Robert's and Henry's two large warehouses in Bishopsgate and also their factory in Suffolk. However, all of a sudden, my searches threw up the story of William Parnall’s wife (William being my bankrupt direct ancestor). But, rather than being a story about the Parnalls, this was the story of his wife, Mary (also my direct ancestor) and her sister, Emma. Both were the children of the very respectful schoolmaster of Grundisburgh, Suffolk and his equally respectful wife, Mary and Nathaniel Redit (my 4x great-grandparents).

The Redit's story starts when William was an up and coming successful businessman – long before his financial woes – and long before his brothers Robert and Henry were even old enough to come to London to seek their fortunes. According to newspaper reports dating from 1833, William's wife, Mary Redit, was "

extremely well married, and living in London". The Parnall siblings' father, Edmund Parnall, was a tenant farmer in Wales and could hardly be described as well-to-do. Therefore, William had, by 1833, become so successful that Mary Redit had married "

extremely well". The story of the Redit women was told through the eyes of local and national newspapers. Reporters delighted in recounting an extremely scandalous and juicy legal story of unrequited love whilst it was played out in the court-rooms of Bury St Edmunds. The story of the Redits even made

The Times newspaper and was probably debated over the breakfast table of many middle and upper-class houses! According to reports, the court-house itself was packed and

"the ladies, to the infinite disappointment of their curiosity, were ordered out of the court."

The Redit women of Grundisburgh, Suffolk

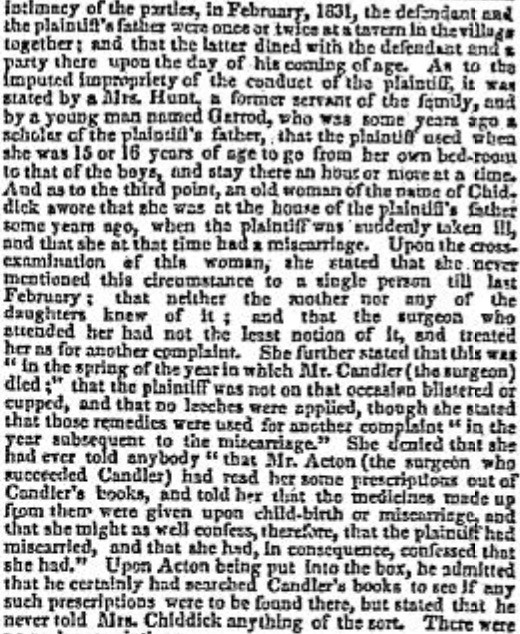

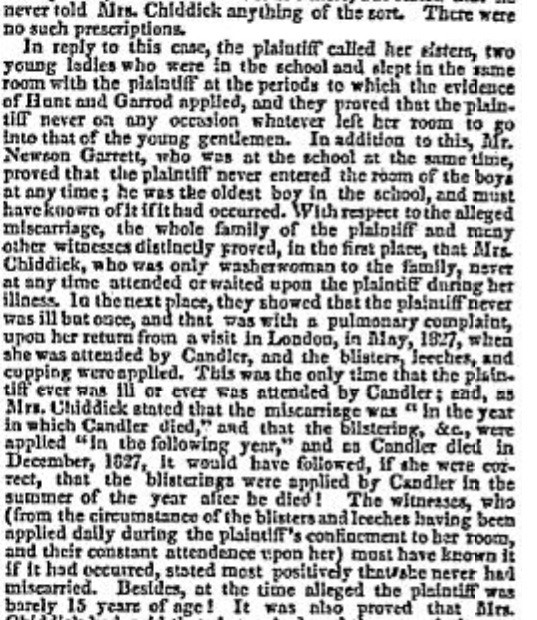

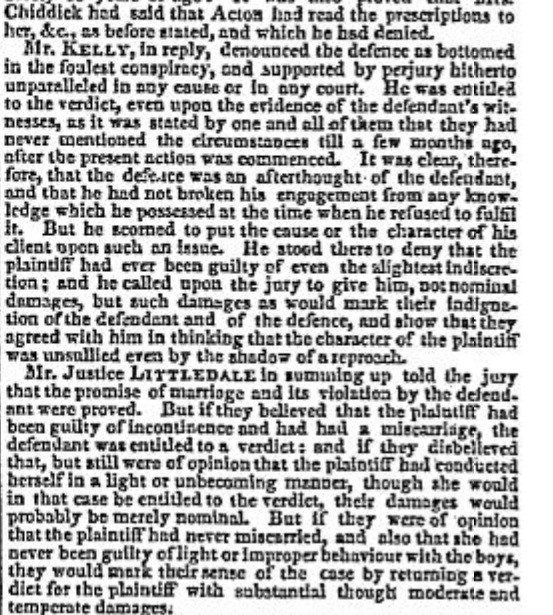

The newspaper account below is from

The Times newspaper for Tuesday 6th August 1833. Emma's case was also reported in the national newspaper,

The Observer, along with all the local East Anglian newspapers.

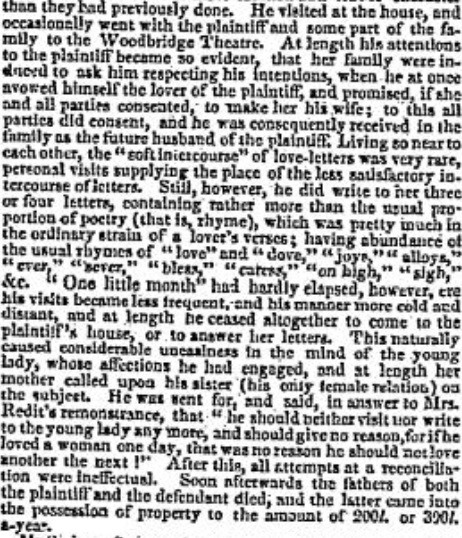

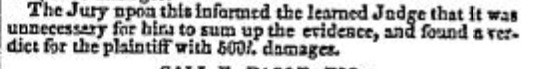

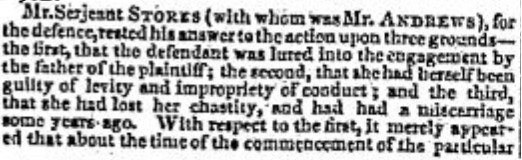

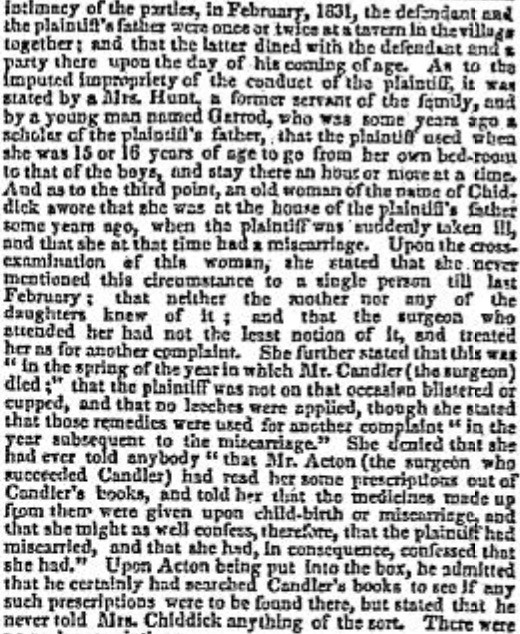

By awarding Emma £500 in damages (a substantial amount in 1833), the judge and jury clearly believed that Emma had not misbehaved, nor had she had a miscarriage. So was not of loose virtue. She was vindicated, and her potential suitor had been found guilty of the civil crime of Breach of a Marriage Contract.

Emma’s breach of marriage was retold in even greater detail in the many different local newspapers - each newspaper relaying different aspects of the case. Her mother and her 4 sisters (including Mary Parnall nee Redit) had all been called as witnesses. Many of the newspaper reports recorded their testimonies as to their own and Emma’s behaviour. This case was not just about Emma’s good virtue, but it had put into the question the entire Redit family’s morals. Emma’s mother, Mary (my 4x great-grandmother) seems to have been on the witness stand for a long period of time and she, out of all the Redit women, was personally held to account by barristers acting for Lucock.

Mary Redit testified that:-

“I am mother of Emma Redit, who is my third child. My two elder daughters are married [this included Mary Parnall]. Emma is now 23. My husband died in February 1832; he kept a school at Grundisburgh 26 years. Defendant’s family had lived at Grundisburgh 30 years; we were intimate. Mr Lucock’s family consisted of a daughter and son. Mr Lucock [father] died in July 1831. Defendant was a scholar at my husband’s school, he was about 13 years old when he left. Defendant continued to live at the house where his father died. Mrs Grimwood (defendant’s sister) died about the end of last year. Defendant’s [Lucock] visits were frequent at my house about February and March 1831. We considered him as the intended husband of Emma. He came there much more frequently than he had previously done; and he paid more marked attentions to my daughter. He took her to Woodbridge Theatre, with her younger sister. My daughter was much attached to the defendant. [Note in the newspaper’s account: Letters were put in [to court] and identified as being in the handwriting of the defendant]. One day my daughter said she should like a letter on a plain piece of paper better than one he had given her; and he gave her another letter in which he promised to make her his wife. At that time and afterwards he was received in [the] witness’s family as her daughter’s future husband. Witness heard defendant say, he should not have a house to seek for, as he had one, and an income. He said the house was left in his father’s will to him (this was before his father’s death). He said rather more than half the property was coming to him. The latter part of March, defendant’s visits became less frequent. (Another letter was then put in [to court] and read, in which the defendant apologized for omitting to perform some engagement). When his visits were less frequent, I called a third time on Mrs Grimwood; it was not till I called a third time on Mrs Grimwood that I saw the defendant. I than asked him what he meant by not paying his visits to my daughter, as he promised; he had promised to take her to the theatre. I asked him why had had not answered my daughter’s two notes. He said, he never intended to come or to answer any notes. I asked him for his reasons, and he said he had none. I told him he must have heard something***; he replied he, he had not. He said, he never intended to make any explanation of his conduct, for if he loved the girl one day, it was no reason he should the next. I asked what he had done with the notes; he said he had burnt them. Defendant never renewed his acquaintance with my daughter after this period, and he never assigned a reason for his conduct.”

***My note: Is Emma’s mother unwittingly telling

us here that there had been rumours about Emma’s virtue and her alleged miscarriage? Had Lucock heard rumours about Emma - hence him breaking off the engagement?

Mrs Redit was cross-examined by Lucock’s barrister. Through the newspaper’s account of the cross-examination, it is clear that Lucock’s barrister was putting her own name, and that of her late husband’s Nathaniel’s name, into disrepute. Thus, the entire Redit family was on trial. Moreover, the implications are clear in the newspaper reports: Lucock thought Emma and her family were gold-diggers and after his money. Mrs Redit testified that:-

“My husband [Nathaniel] did not die in very good circumstances. I did not dictate the letter produced. Nothing was said about a stamp for that letter. [This appears to have been the letter where Lucock had declared that he would marry Emma] Young Lucock kept his birthday at the public-house, called the Dog; I was not there. I never took wine or spirits at that house in an unbecoming way; never took more than two glasses. I may have gone to the public-house sometimes three times in the year. Defendant came of age on the 22nd and gave the promise of marriage on the 28th. I never saw defendant intoxicated in my life. He came home with my husband about three o’clock one day. They came to have a beef steak together, they had a little wine.”

The implication above was that Mrs Redit had made young Lucock write the letter of his intention to marry Emma whilst he was drunk after a heavy drinking session with Mr and Mrs Redit on his 21st birthday. The landlord of the Dog public house was called as a witness to repudiate Mrs Redit's testimony. He testified that:-

“The defendant’s birthday was kept at his house [i.e. The Dog] in February 1831: eleven people were present and Redit [i.e. Nathaniel, Emma’s father] and the plaintiff left the house [pub] together and proceeded to Redit’s house. Mrs Redit was once at his house in company with Captain Drury (since dead) and her husband, and on that occasion drank nine glasses of sherry. He saw her take five, and the Captain said she had drank nine”.

(An eyewitness account of five sherries - but more than likely nine sherries!!! My 4x great-grandmother seemed to have liked her drink!)

In the end, as we have seen, despite all the mud-slinging, Emma's good name was proved, and she won her case for breach of marriage. It must have been unbearable for this family to be thrown into such an intense spotlight. Even though Emma won her case, the Redit name must have been ruined locally. After all, as the old saying goes, there is no smoke without fire... Emma's story could have ended here, despite her winning in court, her good name and virtue (and that of her family's) ruined forever and her reputation in tatters. She must have been very notorious, and would have had extremely poor marriage prospects.

The Redits of Suffolk and the Parnalls of Wales

However, Emma’s story did have a happy ending. On the 7th August 1836, three years almost to the day after the court case, Emma married her sister Mary’s husband’s brother, Robert Parnall in Soho, London. (I wonder if the date of her marriage was merely coincidence? Or did she use the date to reinforce the message that she was the innocent victim of scandalous gossip...) This was the very same Robert, who, as I previously recounted further up this post went on to find his fame and vast fortune on the streets of London. At the time of their marriage Robert was 20 and Emma was 26 years old. Whatever earlier escapades Emma got up to, the Parnall family obviously believed her story and all the Parnalls stood by her and the other Redit family members. Emma died in the 1860s and lived much of her life in London, Brighton, and Llansteffan as a rich wife to a highly successful and well-connected Victorian merchant. It is not a far leap of the imagination to speculate that Emma’s £500 damages from her breach of marriage to Lucock might have been used to found the Parnall’s substantial business empire.

The newspaper reports show how close the Redit family had been, and how they all testified for Emma and her virtue. It is perhaps of a consequence of this that when William Parnall was made bankrupt in 1847, his brothers and their wives stuck by him and supported his vast family for many many years. The Parnalls and Redits were doubly related with sisters Emma and Mary marrying brothers Robert and William; and they really did look after their own. When Mary fell on hard times with the bankruptcy of her husband, Emma must have repaid the debt of the sisterly loyalty by financially supporting Mary's children (and even later, Mary's grandchildren) through the businesses of Robert and Henry Parnall. They say that revenge is best tasted cold. Emma certainly did get her revenge on Lucock: the Parnalls became so much wealthier than Lucock could ever have imagined. Emma was far from the gold-digger Lucock accused her of being, as Robert Parnall was not wealthy when they married. But, she did became fantastically wealthy through the business of her incredibly successful husband.

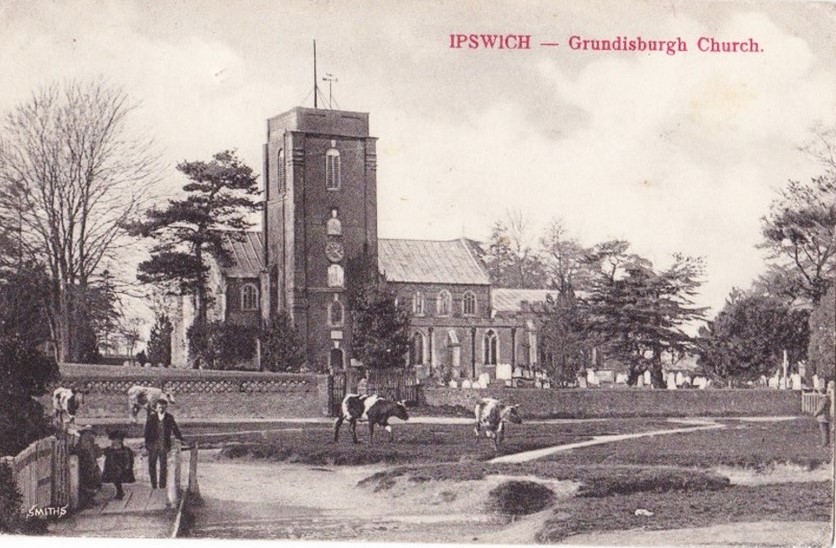

Grundisburgh churchyard, Suffolk

During my years researching the Parnalls, I have come across many “internet cousins” who have researched various parts of the Parnall story (although I am the only one to have tracked down Emma Redit’s story and her breach of marriage contract court-case). One thing that has always puzzled all of us is why did Robert and Henry Parnall set up a large clothing factory in the rural Suffolk village of Chevington when they were all from Wales? This factory in rural Suffolk, at its height of success in the 1850s, employed over 600 people! That is a tremendous number of people for a tiny rural village, although, most workers were probably women working piece-rate in their own homes.

The story of the Redit sisters from Suffolk and their marriage to the Welsh Parnalls part way gives one explanation why the Parnalls might have set up their clothes-making empire in Suffolk.

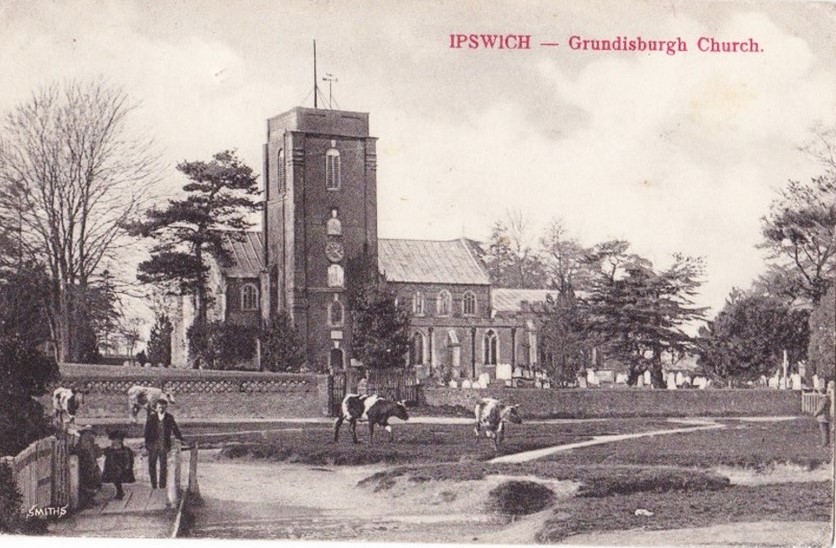

But, perhaps even more reason for the Parnall's connection to Suffolk, is the tiny grave I discovered this summer in the churchyard of Grundisburgh's parish church – a tiny grave laid next to the grave of Nathaniel Redit, schoolmaster of Grundisburgh. Nathaniel, the father of the scandalous Redit sisters, and the husband of the sherry-loving Mary Redit. The tiny grave next to Nathaniel's is that of an infant, Robert, the eldest child of Robert and Emma (nee Redit) Parnall. Long before their vast riches came their way, their first born child died as an infant, and instead of being buried with his father's Parnall family in Llansteffan in Wales, was laid to rest in the tiny Suffolk churchyard in Grundisburgh – the home of the Redit family.

|

Nathaniel Redit

School master in this parish 30 years.

Highly esteemed.

Born 17th July 1778. Died 8th February 1832. |

|

Robert Redit Parnall.

Infant son of Robert & Emma Parnall of London.

Grandson of the late Nathaniel Redit school master of this parish.

Born 16th June 1837. Died 16th January 1838. |

It is interesting that Nathaniel was "

Highly esteemed". With his death occurring just 18 months before his daughter's Emma's court case, it could be speculated that his headstone was put up after the court case (perhaps at the time of the infant Robert's death) and, with his epitaph, the Redit's were, once again, asserting that they were a respectable family. The infant Robert's epitaph also shows that the Redits and Parnalls still considered themselves to be firm respectable members of this small rural community. Robert Parnall was an extremely shrewd business-man: it might have made considerable financial reasons to have part of his empire so far out of London in rural Suffolk. But perhaps even more so, he was appeasing his wife, the redoubtable Emma (nee Redit) so she could visit her two sisters still living in Suffolk, and visit the grave of her only child, Robert Redit Parnall.

Of Emma's hapless one-time suitor, Lucock, I know nothing further. Not even his christian name.

This is a warning to all genealogist everywhere – follow up your female family line – you never know quite what you’ll find. Your ancestors, like mine, might have been the subject of many heated debates conducted over the breakfast tables of the great and good from nearly 200 years ago! I am very proud of my sherry-loving 4x great-mother and her four daughters - the Redit women of Grundisburgh, Suffolk.

|

The Dog Inn, Grundisburgh.

The location of Lucock's coming-of-age party when he drunk heavily with Emma's father,

the school-master Nathaniel Redit. Also the scene of Mary Redit's tippling of no less than 9 sherries in one session. |

|

| The village of Grundisburgh on a postcard from the early 1900s - some 70 years after the scandalous events of the Redit women. The school on this postcard is still there in the village. However, as it was constructed in the Victorian period, this was not Nathaniel Redit's school. The village of Grundisburgh is tiny, it is therefore possible that Nathaniel's school was located in roughly the same position as the later Victorian building. |

|

| Grundisburgh Church. Underneath the round tree on the right of this picture lies the remains of Nathaniel Redit and his baby grandson, Robert Redit Parnall. There is a tree at this location today (probably the same tree as the one in this Edwardian photograph) and this tree has ensured that Nathaniel's and Robert's graves are relatively untouched and unmarked from nearly 200 years of standing in a rural churchyard. Their graves having been protected from the elements was there waiting for me, their direct descendant, to find and finally link together the story of the Parnalls of Llansteffan, Wales and the Redits of Grundisburgh,Suffolk. |

Remember back in January when I told you that my own

Family history is like a box of chocolates - you never know what you're gonna get? Well, the story of feisty Emma Redit, her (clearly non tee-total) mother and her loyal sisters are among the best and finest chocolates in my box of chocolates!

*_*_*_*_*_*_*_*_*_*_*_*_*_*

I look forward to sharing with you more of my discoveries over the coming months - see you next time on this blog on 18th October 2014. In the meantime, you can catch me on my blog

Essex Voices Past or on twitter @EssexVoicesPast

You may also be interested on my previous posts on this blog

-

April 2014: Happy Easter 1916?

-

March 2014: Who do you think they were?

-

February 2014: Family History Show and Tell

-

January 2014: Family history is like a box of chocolates - you never know what you're gonna get

I have written more about my Parnall ancestors here

-

The Coles of Spitalfields Market

©

Essex Voices Past